Soul from the periphery

The premises of the Premonstratensian monastery in Želiv in the Highlands served the patients of the psychiatric hospital for over 30 years, and traces of it remain there to this day. Today, the lives of their residents are reminiscent of solitary confinement, treatment baths, a room for hydrotherapy, or scratched walls… Psychiatry in Želiv, originally intended as a rehabilitation center for neurotics, was opened in 1956 after the necessary modifications and occupied initially by female patients requiring long-term treatment. From that time, the history of the treatment center began to be written, lasting until 1991. Gradually, three primaries were established here, focusing on general psychiatry, sexology and anti-alcohol treatment.

The new exhibition entitled Soul from the Periphery, which was created here, is located in the part of the monastery of Trčka Castle, where the women’s department of the psychiatric hospital used to be. Female patients are also the main subject of subjective photographs, whose expressions were lovingly captured by the former primary MUDr. Bořivoj Vejr, who spent most of his professional life here. In other, older photographs from the 1960s, women are captured reading newspapers, playing board games, crocheting or plucking feathers.

In 1974, MUDr. Bořivoj Vejr was elected to the position of chief of psychiatry. One of his great hobbies was black and white photography. The interesting subjective portraits of the chief’s favourite patients in this room are from the period of his work in the women’s psychiatric ward in the 1970s and 1980s. His perceptiveness and talent resulted in visually clear and unique shots from the perspective of a therapeutic physician and sensitive human being. Few of us can create artistic records of reality free of stigma while maintaining a restrained and peaceful acknowledgement of inner anxiety, fear or other feelings that remind us of the nature of the life we live. The defining moment of human observation here is the authentic experience of what can bring among us a certain sense of difference that makes us wonder or question. In this way, his “images” draw us into the world of the lives of people living in a somewhat different world that for most of us is still separated by a barrier.

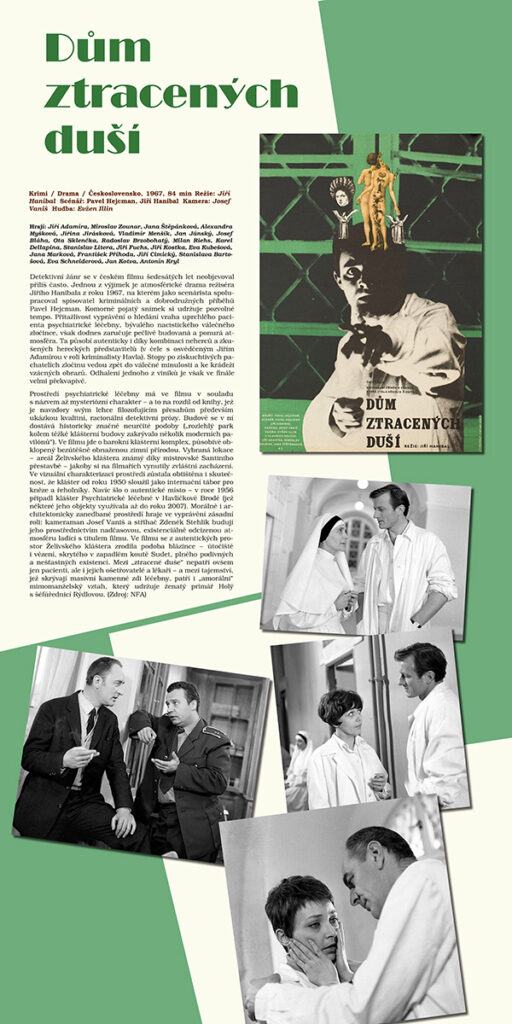

The environment of the psychiatric hospital in Želiv was also chosen for the filming of two movies. First, it was a 1960s detective drama directed by Jiří Hanibal – “Dům ztracených duší”, the Želiv monastery and its baroque complex impressively surrounded by bleak winter nature created an authentic place for filming with its mysterious atmosphere hidden somewhere in a remote corner of the Sudetenland…

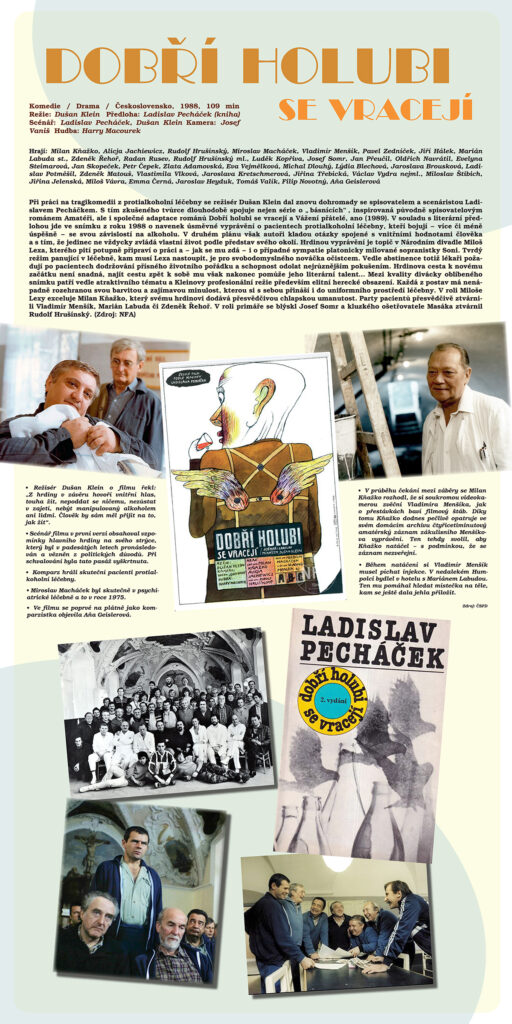

The second film from director Dusan Klein – “Dobří holubi se vracejí” is a story set in the environment of an alcohol treatment centre. It is an outwardly funny story about the patients of an alcohol rehab who are struggling with their alcohol addiction. However, on the other hand, the authors here raise questions related to a person’s inner values, which are not always in line with their surroundings.

To conclude these facts, a few words from the memories of the now deceased Chief Medical Officer, Bořivoj Vejr, MD: “The psychiatric hospital in Želiv took care of needy souls for a total of 37 years. It seems that nothing remains of it today except the memories of the people still alive today. But hasn’t an understanding for people in need, for weak people succumbing to their delusions and anxieties, begun to germinate in many of the staff here? Or the weaknesses for which they were often condemned and punished? Who among those who have taken it upon themselves to care for them would elsewhere have the opportunity to look beneath the surface of their sick souls, their actions, to know their weaknesses and sometimes the causes of those weaknesses for which they could not help, because they were not endowed with the strength to overcome them? And from the other side, perhaps some of those who were taken here, often against their will, took home with them the knowledge that there were people walking around the world who did not condemn them, but who tried to understand and help them in their human misery. Even for the stone walls of the monastery itself, it was perhaps not an entirely futile coexistence. At a time when suffering people were moving here, it could have been decided somewhere that tons of fertilizer, for example, would be stored here, or something worse would happen that would affect the continued existence of the entire monastery.”